Yom Kippur War in the Sinai Desert – 40 Years After

Rabbi Michael Graetz

This desert has seen myriads of people dying in its sands

By starvation, by sword, by fire and by water;

This desert has felt 600,000 pairs of feet walking its paths;

And one prophet climbing a mountain midst lightning and thunder

To bring a newly freed nation a Torah by which to live.

I saw people die in this desert;

I saw letters from the dead to wives and children, to parents, brothers and sisters,

I saw wounded being healed, and I heard them give thanks for their lives;

I saw soldiers running toward death to save friends;

To protect their homes and country,

And, I saw strangers, not part of the war, who came to impose peace and stop death.

I saw two peoples give honor to each other,

They returned bodies of soldiers in order to comfort families and a whole nation,

I saw the possibility of humanity between enemies,

The ability to feel a common destiny among those who had fought cruelly,

May these memories arise with the night,

May our rejoicing shine with the morning,

And may our joyous song continue until the evening.

After 40 years some things become clear that were not even seen before, even though the process that brought them about had begun. The main thing that has become apparent, to me at least, is that the war between Israel and Palestinians [actually with all of the Arab world and most of the Muslim world] is really two wars intertwined with each other, pretending to be just one war. It is a mistake to forget or overlook or underestimate that the characteristics of these two wars, aside from the fact that they are wars, are totally different from each other.

One I will call a “classic” war over territory and rule over it, including economic consequences and control over natural resources. The Yom Kippur war was of this type. Viewed that way, the best outcome of the YK war was the peace treaty with Egypt, and in its wake with Jordan. Returning territory brought about peace, as in most ‘classic’ wars. There was a concrete subject for negotiation, there was something to give up, and after negotiations a peace treaty was achieved which has lasted until this very day [despite many possible points where it might have ended.]

The second type of war is a “religious” war, where ‘religious’ refers to specifically to a religious stream which is extreme and zealous. The motivations for this kind of war are zealous and extreme religious beliefs which are perceived by those who hold them as absolute and unbending. Thus, there is no room for negotiation or giving in, for in the end the belief which absolute and it is forbidden to change this belief. The only result of such a war, for the believer, is either surrender, religious conversion or death.

In in a “classic” war it is possible to bargain and reach agreements that will lead to peace, or at least to the ability of two peoples to live side-by-side without fear of aggressive attack or terror. In a religious war there are no interests upon which one can compromise, there is no cold logic nor any computation of loss or profit. In religious war the major motivating factors are martyrdom, revenge in the name of the Lord, the defeat of evil religion, idolatry or some form of foreign worship. In a classic war one may conduct conferences whose goal is through negotiation to achieve compromises which would be acceptable to large populations. In the religious war the slogan is “may my soul die with the Philistines”, and all under Divine approval.

For a person who does not fully appreciate or understand the seriousness and commitment of people to extreme religion it is impossible to imagine what religious war is like. Unfortunately, for those of us who live in Israel we have too much bitter experience to not understand that religious extremism is negative, and that a religiously extreme group speaks in the name of a whole religion, even though that group may be a small part of the whole religion.

In the wider Arab Israeli Muslim conflict these two different types of war are woven together, and the question is in what way are they interwoven. One may claim, for example, that the desire of some countries to remove Israel from the Middle East as a state is based basically on religious motivations, but a certain small percentage of the conflict is also about territory and rule over Arab populations who reside in that territory. Thus, those who claim this understand the conflict is primarily a religious war. Note however that this approach is more or less appropriate depending on the country’s one is analyzing, and there are even examples of inner conflict within an Arab country over granting authority to religious extremists, for example, Egypt.

However, the Yom Kippur war was primarily a classic war, where the religious component was in the background as a minor part of the Egyptian self-image as a state which was the leader of the Arab world, even though many Egyptians did not see themselves as Arabs. The outcome of the Yom Kippur war was, as we know, the return of territory, which did not include any factors of control of Arab populations, and the destruction of any sign of Israeli “presence” in that territory, in exchange for a permanent peace treaty which included diplomatic relations. At that time a systematic Muslim religious war against the Judeo Christian world had not developed to any great degree. Only in subsequent years did that system develop until the event which changed the perception of Muslim extremism, the attack on the twin towers in New York.

Let us return to 1973. A big question remains: what were the factors that lead the Egyptian leadership to come to the conclusion that they needed to conclude this war through negotiations as the style of a ‘classic’ war? Of course, there are many possible answers to this question. I want to propose two possible answers of my own thinking based on my experiences during that war and after the ceasefire.

The first answer that seems to fit, in my mind, is that Egypt saw itself as victorious in the war. However, at the same time, they reached a strategic conclusion that they were not capable of totally defeating Israel, that they could not remove Israel from the Middle East by military force. I assume that Sadat and the military leaders came to that conclusion based upon the fact that despite their superiority of numbers, and despite the element of surprise, and despite the fact that they managed to overrun Israel’s defense line and conquer substantial territory in the Sinai that had been under Israeli control; in the end they were pushed by the IDF, and brought to a low point in terms of territory that had been under their control, and many Egyptian soldiers were trapped. Their analysis of the relative might of their military versus the IDF was simply realistic. They did not perceive any contradiction between their feelings of victory versus their cold analysis of the possibilities of future wars.

In this matter it is fascinating to note that Israelis always perceived themselves as losers of this war. The prevalent feeling in the Israeli public about the Yom Kippur war was one of defeat and failure, even though from an objective point of view it was perhaps one of the greatest comebacks in the history of warfare. From a beginning of failure and defeat the IDF managed to capture substantial enemy territory and defeat their armies. However, perceptions and feelings seem to be so important that facts have no power to change them.

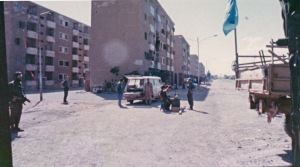

The second answer is not so widely known as the first. It has to do with the psychology of soldiers who have participated in a war, more accurately the effects of soldier’s experiences in war on their psychology. I include in this all soldiers who took part, including the military leaders and even political leaders. After the cease fire, supervised by a UN force, a system of relationships between Israeli and Egyptian soldiers developed on all levels of command. Since I was a native English speaker, I became part of the many meetings between Egyptian, Israeli and UN officers as a translator. I was present in these meetings from the very beginning when they began in the middle of a street in the city of Suez.

The UN post in Suez: Israeli soldier bottom left Egyptians under building

More importantly, I was also present at some meetings in Ismailiya where an Egyptian officer raised the possibility of a mutual exchange of fallen soldiers by each side. There were protracted discussions filled with emotion and the arrangements to transfer the bodies of fallen soldiers from Egypt to Israel, and from Israel to Egypt. The transfers took place on the 101st kilometer from Suez to Cairo. They received some coverage in the press at the time, but I know of now in depth examination of those events. Only after all this time, in the last year, I have begun to rethink about those experiences, and find that I am interpreting much that occurred after the war in the light of that special occurrence “the transfers”.

Km 101

As I reflected on the meetings and the ‘transfers’ I began to realize that a kind of atmosphere of soldier’s honor developed between the Egyptian and Israeli officers, even a certain admiration and camaraderie for the humanity of the “other”. This psychological development occurred even among noncommissioned soldiers, but, to a lesser extent because they did not experience long hours of being in discussion with the “other” but rather only sporadic moments at the ‘transfer’ point. But, even that was enough to spark an awareness of the humanity of the other side.

I believe that it would be a mistake to underestimate the importance of this development. Perhaps, because of the ‘transfers’ and the process of meetings that made it possible, the Egyptian leadership, in addition to a simple conclusion that they would be unable to conquer Israel based on a cold realistic analysis of the skill level and power of the respective armies, also developed a tendency to sympathize with Israel, a tendency to respect them not only as soldiers but also as human beings who reciprocally respected them as human beings. This same process of developing some form of sympathy and respect occurred among the Israelis vis a vis the Egyptians. I was present during many meetings where I felt that the default norm of Israeli mistrust of and looking down at Egyptians as people, changed into a different norm of respect and some semblance of trust because they were, on their own initiative, returning our dead to us, and they were doing it with clear honor and emotion. At the beginning of these talks we told ourselves that we had to return Egyptian dead in order that they return our dead to us; but as time and the planning of how this was to be done went on and the talks continued we learned that they had much more humanity than most people thought; and we understood from things said in the talks that they were undergoing a similar psychological process.

My unit, the IDF Hevra Kaddisha, dealt with Israeli dead and buried them in temporary cemeteries with the intention of transferring the remains after one year to a permanent grave in each soldier’s home cemetery. At the same time we collected Egyptian dead and buried them similarly in temporary graves, with the idea being that each one could be used as a bargaining chip in order to gain return of one of our dead held by the Egyptians. But, when these talks began it was soon clear that there was no thought of negotiating over a particular soldier’s remains, rather there was a military code of honor and a genuine humane desire to return all of the fallen from one side to the other. I remember how emotionally difficult it was to uncover and transport fallen Egyptian soldiers, but how we understood that it was our duty to do so, for not only we deserved to have our fallen returned to us, but they also deserved it.

Transfer of an Egyptian soldier home

I have no research to prove my feelings, but now as I reflect on past events and experiences of this very difficult war for the nation of Israel, I see a turning point in our ability to reach understanding with certain countries in our region. I am not at all certain, but it is very possible that the sparks of humanity and mutual respect that were generated by the talks about ‘transfer’ of fallen, and even strengthened by the actual implementation of the ‘transfers’ at Km 101. Perhaps these sparks remained in the memories and in the hearts of Egyptian officers and even in the state officials, particularly Sadat, who also were part of major decision to do everything to achieve a peace agreement. Our great fortune was that Menahem Begin, z”l understood the possibility of a genuine achievement for the long run, and was not afraid to make the leap of faith in other people, even in people who had recently been enemies.

The Mishnah explains the main feature of Yom Kippur thus: “For transgressions between man and the Lord the day of atonement procures atonement, but for transgressions between man and his fellow the day of atonement does not procure any atonement, until he has pacified his fellow.” (Mishnah Yoma 8, 9) There is a condition for atonement and forgiveness, for attaining a pure soul, to pacify one’s fellow whom you have offended, the ‘other’ whom you have hurt. Until that condition is met, Yom Kippur has no effect whatsoever regarding atonement or forgiveness.

I now realize what I felt and understood at Km 101. It was the potential of human beings, even of those who only a short time before were killing each other, to come closer to one another, and even to help one another cope with pain and loss. I was a witness to how human beings are capable of learning how to live with neighbors, even neighbors who have hurt us. That possibility, that ability is implanted in human beings by God. One of the main goals of Yom Kippur, as a religious holiday and ritual, is to expose us to this potential within us. It is to say it out loud and bring the possibility to the forefront of our consciousness. The ritual acts of fasting and creating a sacred event join together to grant us a moment in which we begin to believe that it is within our power and capability to ask forgiveness from the ‘other’ whom we have hurt, and it is also in our power and capability to forgive the ‘other’ for acts he has done which hurt us. I witnessed moments of that belief, that faith in our capability to forgive and live together, during the ‘transfers’. I continue to wonder if perhaps those feelings trickled down and remained in the souls of Israelis and Egyptians who were there. Thus, according to this feeling, it is extremely appropriate to name this war “the Yom Kippur War”, not only because it broke out on that day in the Jewish calendar, but more importantly because one of the outcomes of this war was peace, and a de facto ability to live together in spite of past wrongs.

God who ensures peace in the heavens; help us to ensure peace in our region, and for all of the nation of Israel, and for all nations of the world. Amen